Hi Scott,

Bonjour! The easiest way I could work out to share the music, text, and pictures that amount to my Cross Cultural "Artifact" was to build a webpage. This is an unlinked page so it will only work for people who have the exact url. As you scroll down you should be able to play each track I've recorded and then read the "liner notes" and see some related images as you listen. I hope you enjoy!

Tom

Prélude de l'anticipation

I recorded the first guitar part for this track on the ferry crossing from the Portsmouth to Caen. We had landed at London Heathrow the previous morning, hired a car, and somehow managed to make it safely around the M25 and down to Portsmouth for some time with my former Vicar, Gavin and his wife, Christina. They were the perfect start to the trip, praying with us, and helping us stay awake to fight the jetlag. They sent us off with a box of goodies for our travels and soon we were sailing off to France. Even though we were tired, neither of us could sleep on the 5 hour ferry journey. This trip has been several years in the making and we were full of eager anticipation. We were excited to see and experience more of this country that we love. We were also nervous as this trip was rather different than a holiday. The added weight and pressure of considering a long term move to the places we were experiencing made our time feel different. In a way, it was a perfect fit for a cross cultural experience because considering what long term living would be like quickly blows away the “isn’t this lovely” holiday maker lens. We were looking for real life and in so doing we saw much of what will be so hard about living cross culturally. But on that ferry ride, we were simply full of nervous energy and anticipation. I recorded that first guitar lick as a scratch track trying to capture some of the emotion of the moment, with the intention of re-recording later. Even though it wasn’t perfectly played, I eventually decided to keep the first recording because it really did capture some of the energy of that initial crossing. If you listen at the beginning you’ll hear the drone of the big diesel engine pushing us across the channel towards Normandy.

C'est Notre Dieu

We were met in Caen by Gerard and Chrissie Kelly, who are the leaders of a ministry called Bless that seeks to plant international (bilingual) churches in Normandy and North Western France. We walked around the city together and soaked in the interesting mix of cultures that often exist in a port city. Then we were off to Bethanie, the ministry base for Bless. Bethanie is a old cider farm which has been repurposed as a prayer room, home for interns and staff, and meeting place for a church. We had an amazing dinner with Gerard, Chrissie and a couple of their French friends, Thierry and Michelle. I started to notice that even things like having dinner exhausted me more than it would have in the states. Some French was spoken and I was pleased by how much I could understand (I’ve been working on this), but it wasn’t just the language or the weirdness of greeting everyone with kisses on each cheek that was tiring. Everything was different. It reminded me of our initial moments in the UK where we had lived for five years some time ago. I remember learning at the time (although I forgot this principle while scheduling this trip) that I simply didn’t have the same capacity for interaction or ministry work that I did in the States. In time, that shifted a bit, but I still think that those who minister cross culturally must accept this limitation or risk burn out. This got me thinking more about the nature of cross cultural ministry and whether it was worth it. If a French pastor can have more capacity for ministry work and doesn’t have to overcome the incredible handicap of language and culture acquisition, why not simply raise money to support them? Is the cross cultural missionary model outdated, a dinosaur destined for the colonial scrapheap? There are certainly many who would say yes, in fact I have recently learned about a missions organization that instead of sending missionaries, selects leaders from within a country and trains them. To me, it is easy to see how this is still an incredibly patronizing method – “we want your people to come learn the real way to evangelize and plant churches because clearly you suck at it and the newest American models will of course work in your country.” All of this was going through my head and ultimate leading me to a really important question – A question that has been bouncing around in my mind for the entire time we’ve been getting ready for this “vision trip” though I think at times I didn’t want to give it voice. Do I believe that there is value enough in being fully focused as a cross cultural missionary to warrant uprooting and moving my family and inviting people to support us in prayer and with finances? It was in this head space that we were asked to lead worship at the Sunday service in French and English. For this track Joanna and I have recorded the song that we liked best from that worship set.

C'est Notre Dieu

Reuben Morgan

This Is Our God © 2008 Hillsong Music Publishing

Le blues de la ville

The second half of our trip in France was spent visiting cities and on a retreat with the Greater Europe Mission (GEM) team in the Alps. We visited Angers, Grenoble, Lyon and Chantilly trying to get a taste of what life and ministry might be like in each of these cities. We definitely overbooked ourselves! We did love the cities, especially Angers which is where we are going to be based long term. Also we found GEM to be a great fit as a team for us. We had some concerns going in about the role of women in ministry and about whether our vision for cross cultural engagement would fit with GEM. We found a diverse yet united team of people and were please to see that each missionary family were free to lead and minister out of who they were, rather than fitting into a mold.

In my second week in France I was feeling much better (jetlag had subsided), but I was also remember some of what had made me feel affirmed in a calling to cross cultural work in the first place. It is a hard calling, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t right. I believe there are things I can say, do and be in ministry as a foreigner that someone who is from within that context cannot. I also think the body of Christ is made strong as people intentionally go out to learn and experience another culture. This track is a happy blues. There is a reality that in cross cultural ministry, one is never quite at home. Yet, I loved praying in the city streets, soaking up the language food and culture. There is joy and sadness inherent in crossing cultures.

Le Passage

I wrote this essay first and then recorded the music as soundtrack for this crazy experience.

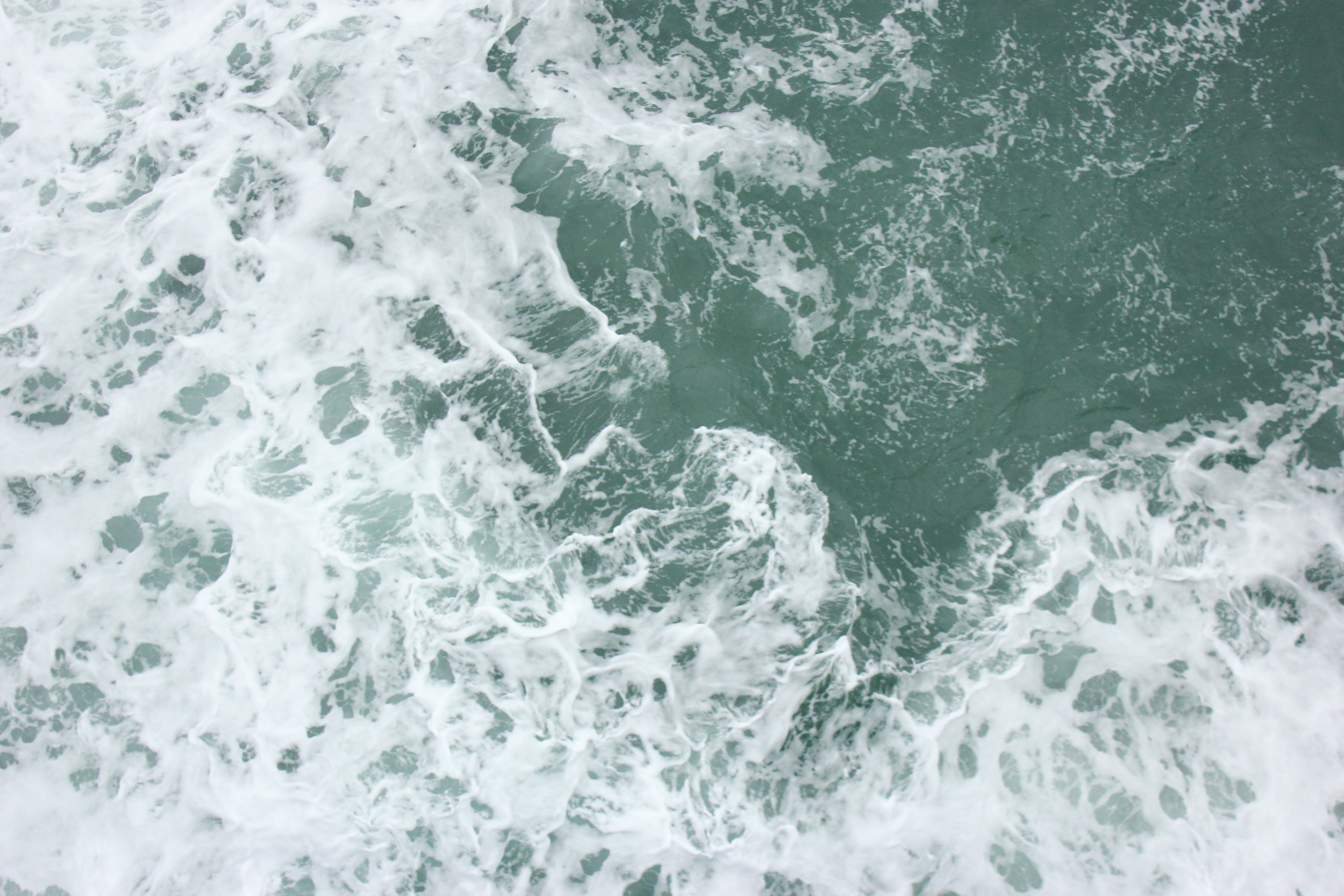

The spray, salty and stinging, is welcome relief. I join the ranks of other travelers leaning heavily on the railing staring hard towards the horizon. There is no horizon really, just the abrupt end of gray sea into slightly less but still angry gray sky. It is raining hard, but we all think it’s better out here in the cold wet air. The ship doesn’t move forward and aft, or up and down like a carousel horse. It corkscrews through the water in unpredictable chaotic motion such that it is easy to find oneself unexpectedly against a wall. Inside the movement is somehow amplified, so we staggered through the narrow corridors and burst out to the observation decks in a doomed effort to escape. There is no getting off mid-journey. “Take the ferry,” they said. “It’s cheaper, and the Chunnel train is being canceled almost every day because the refugees try storm the tunnel and make their way to England.” I curse their bad advice and pretend not to hear the person to my right being sick over the rail. At the refugee camp in Calais called “the jungle” there are groups of men who walk over an hour each day to try and jump on a train or lorry heading through the tunnel to England. Some of them die or lose limbs in these attempts. They began their journeys in Northern Africa or Syria and traveled by makeshift boat across the Mediterranean into Europe. So far, 3500 are estimated to have died at sea this year, and the numbers beginning this voyage grow each day. I try to think of these people, my Mom’s voice from childhood in my head saying “there are starving children in third world countries who would love to eat that casserole.” I think about the men in Calais, their rough hands and bright smiles, and remind myself that they would gladly trade places with me. I can’t think, though. I’m trapped in my own discomfort on this Brittany Ferry, The Amorique, as we make our way slowly to Portsmouth on the heaving and swaying seas. I can’t find my empathy on this angry water. A man behind me lights a cigarette. Others pull out smart phones and stare at them as if we had any signal. There is no distraction great enough to hold back the tide of seasickness. The sound of our vehicles banging together from the lower decks is punctuated by the occasional car alarm. As the door opens for others to join us outside, I hear the sound of children screaming. Anxiety creeps in as the sky darkens and the storm gets worse, and now a staff member is calmly asking us to move back inside. Modern ferry boats don’t sink in the English channel, I try to reassure myself. In my fear, I think of the picture: A child, no more than 2 years old, laying lifeless, washed up on the beach, with an Italian policeman in the foreground. Finally a thousand words to wrench the hearts of the world and wake us up to this refuge crisis. I do not pray for them. I am lost in my fear and discomfort and praying only for Portsmouth. God get us to England, God keep us safe, God make the storm stop.

Foi et le Doute

The following is a personal essay I wrote as part of another class I've been taking this semester. Even though it is a bit long, I feel it belongs with this concluding track of the EP. This track is titled "Faith and Doubt". Themes that were stirred up afresh for me during my time in France. Cross Cultural experiences seem to spark deep theological wrestling for me. This trip was no exception.

The 12 in the Boat

“If through a broken heart God can bring His purposes to pass in the world, then thank Him for breaking your heart”- Oswald Chambers

We are thankful that God has broken our hearts for the people and nation of France.

This is the start of the letter that we send you before we call and ask to meet, so that our invitation for you to give can happen in person. Our fundraising coach tells us that over half of the people who we ask face to face will join our support team.

My wife and I have sold our home, along with most of our belongings, and are preparing to move overseas to plant churches in France. The past couple of years have been a deliberate process of discernment for us culminating recently in an exploratory “vision trip” for an intimate look at the mission we will be joining. If we are successful in the humbling work of support raising, then we get to leave everything familiar and leap into a sea of uncertainty, clinging to the life vest that “the one who calls…is faithful.”[1] This sort of action seems to require an unwavering faith, yet I doubt.

In the book of James it is written that “he who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind. That man should not think he will receive anything from the Lord; he is a double-minded man, unstable in all he does.”[2] Yet I find in the Scriptures a litany of doubters that seems to challenge these damning verses from James. Is the struggle to be free from doubt an endeavor in denial? Faking it, pushing my doubts down deep, and pretending that my faith is bigger than it is doesn’t feel honest—isn’t dishonest worse than doubting? On the other hand, it is disingenuous to follow Jesus and not be stirred to the sort of action that propels us headlong into risk and bids us come out from behind our cynical, doubting hiding places.

“Tommy, after the rock opera by the Who”—at least that’s what my Dad always told me. But my birth certificate reads “Thomas” like the doubting disciple. A quick glance at my life, might lead someone to doubt my doubting credentials. I work in the church. A Charismatic/Evangelical church, in fact, where doubt is seen as something to be cast out by the same perfect love that casts out fear. I stand and preach with conviction, and I share what I believe about God with others who don’t think the same way I do. I pray for people to be healed, and after leading youth through a very laid-back catechesis, I baptize them. And I doubt.

I doubt that God is good in light of the evil and suffering I see. Despite my experiences of God’s love, I still doubt that God cares to be involved in my life. I doubt the potency of my prayers and I question the inconsistencies in scripture to say nothing of our hypocrisy as the church. Some days I’m proud to be a doubter, because it makes me feel detached and superior as compared to some of my more passionately charismatic friends. But there are other days, like today, when I’m tired of doubting.

***

I went to a revival meeting once featuring a man who claimed to have a special spiritual gift to impart. I went with my roommate Mark, who was constantly dragging me and my friends, despite our varying levels of reluctance, to see a wide range of speakers all of whom were burning white hot with the fire of the Holy Spirit. No one had pulled out any snakes to handle, yet, but these gatherings were weird—and I say that as a practicing Charismatic. This night’s visiting speaker, a corpulent Australian bloke wearing a three-piece pinstriped suit, talked for a long while. His message was loosely rooted in some scripture about joy, but mostly he told story after story about the amazing things that happen whenever he prays for people. Apparently his audiences are, without fail, struck by “the joy of Lord” and aren’t able to stop themselves from laughing. I walked out once, but I was a college student and my ride was still in the meeting. When I came back in the man of God had finished telling stories and was popping some tic-tacs in preparation for ministry time. He invited everyone to stand and started moving around the room praying for each person. These prayers involved a gentle poking in the stomach, Pillsbury-dough-boy style, and repeated phrases like “let it bubble” and “he he, ha ha, ho ho.”

People started laughing. Not just a bit of laughter; the jolly bloke poked and prayed and nearly everyone fell about in uproarious belly-shaking hilarity. I stared in shock as more and more of this group of about 100 people began chortling, giggling, even snorting in what appeared to be completely uninhibited joy. The person to my left went down with a mouse-like high staccato laugh, the kind that makes you worry about whether they are able to breathe and laugh simultaneously. Then it was my turn. After he began murmuring in a language that resembled most other prayer languages I’ve heard, he started in with the “let it bubble” and the “he he, and a ha ha, and a HO HO!” It was hard not to smile, but I also didn’t feel anything abnormal. My only urge to laugh might have come from the ridiculousness of the scene all around me, but, in fact, this made me feel more like the outsider in a group with a long-running inside joke.

It was taking me longer than others to receive this gift of joy, so a few more gathered around me to pray. Firm hands locked to my shoulders and I felt my weight shifting back as the Aussie moved in closer. I could see the sweat beginning to bead in the cracks on his forehead and was feeling deeply thankful for his decision to take a mint. As he gave the final push that knocked me back into the hands of the other prayers he leaned in close and almost whispered in my ear four words of deepest reprimand: “You think too much.”

***

I know the story. In the middle of a storm, Jesus came walking toward the disciples on the water, and Peter steps out of the boat. So begin countless sermons and Bible studies. Even a wonderfully catchy book title: If You Want to Walk on Water You’ve Got to Get Out of the Boat.[3] But while Peter’s bravado became the archetype of faith, my namesake was hunkered down with the other 11, or perhaps loosing his lunch over the side. What about the faith it took for the ones who stayed (relatively) dry to even be in the boat? Was it not by faith that James and John left their Father and their nets to follow Jesus?[4] When Jesus decided to go visit Mary and Martha in Bethany after hearing that Lazarus was sick his disciples said to him “But Rabbi, a short while ago the Jews tried to stone you and yet you are going back there?”[5] Was it not faith that motivated Thomas, (yes Thomas!) to say in response to this fear, “Let us also go, that we may die with Him”?[6]

There is a question in this passage that is often overlooked, why did Peter get out of the boat? Because Jesus commanded him to? Yes, but before that it’s Peter who pipes up with the doubt, calling out to Jesus “Lord, if it is you, command me to come to you on the water.”[7] In the grand doubting tradition of Gideon, the reluctant Judge of Israel, Peter asks for a sign.[8] Granted it is much riskier to say “command me to come to you on the water” than “make this fleece wet,” but Peter’s great act of faith is still born of doubt. Aren’t they all?

Apart from doubt faith is foolish; it is easily swayed by every false prophet or new idea about God. The very foundations of our faith are built on the good bedrock of doubt. Doubt that the visible world is the end of it. Doubt that our lives are purposeless or that our souls finite.

***

I was so careful not to drink the water. Even the little kids of my host family knew that what came out of the tap was “agua fea” (ugly water). I brushed my teeth with bottled water, and I barely washed my face or hair in the shower for fear of accidentally swallowing. I even went without ice in my Coke when I enjoyed my weekly guilty pleasure—a McDonalds #2 meal. Yet here I was, unconscious at a San Jose hospital while a nurse drew blood from my arm to find out what sort of amoebas had set up shop in me. I had passed out as soon as the needle went into my arm. It probably didn’t help that my body had chosen to get rid of a seemingly impossible amount of fluid in the 24 hrs leading up to the Costa Rican ER. While unconscious, I had such a strong dream that I was back in the States that my dominate emotion upon waking up (and finding myself vomiting as the nurse shrank back in disgust) was surprise that this was all real.

Apparently the amoebas had gotten to me as I walked around my host’s house in my bare feet. A few weeks later I was headed home, earlier than planned. It wasn’t just the dysentery, I felt like I was drifting in Costa Rica. I was unprepared for the challenge of foreignness. When my unrealistic expectations of the impact I could have in culture-not-my-own fell flat, my faith became confetti.

That summer was first real foray into missions work, a two-month internship just outside San Jose. Time has healed a lot of wounds, but is my faith patched up enough to dive back into cross-cultural work? Do our failures of faith, our faltering steps as we seek to follow Jesus, open our eyes to see more clearly the next time? Or does each cut open new holes in our faith so that it starts to look like those strings of paper snowflakes?

***

Peter and Thomas saw the same miracles and received the same miracle-working power. And they both doubted, but differently. Peter’s doubt is inspired by fear, whereas Thomas’ is a doubt built on a lack of knowledge. In both cases, Jesus’ response is not to declare them unfit for ministry or cast them away but to meet them in the place of their doubts and give them what they need to continue as leaders.

Peter is both the rock upon which Jesus proclaims He will build His church and the man whom only a few verses later He reprimands: “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the things of God, but the things of men.”[9] Despite being the one who gets out of the boat, Peter’s faith has a big mood swing near Jesus’ death. Peter’s faith, after all, is as mercurial as the man. He gets out of the boat, and he alone takes the risk to go to follow Jesus to his trial. So far, so faithful. But then, at the eleventh hour, he denies Jesus. But is Peter inconsistent, or just impulsive? He seems destined to jump out of the boat, only to sink, to follow his master to the trial, only to deny him.

Peter suffers a crisis of doubt as he watches his rabbi bound, mocked and condemned before him. Perhaps he doubts whether Jesus still had the power to save him from a similar fate. Yet, he is not remembered this way. Instead Peter is celebrated for his risk-taking—is this something that we mistake for faith? It is admirable, to be sure, but is it the faith of Peter or his personality that we love? If it is the latter, than it cannot make sense for us to feel guilty for staying in the boat. It’s possible that to jump overboard would be something other than an act of faith, it would be an act of disingenuous imitation. I wonder if this is the beauty of faith, that when it is truly expressed it is as unique as a fingerprint.

***

On a cold British night, I begrudgingly walked up the hill with my wife to the Sunday evening service at the Charismatic church where we worked. I had a head cold, and I really just wanted to sit home and watch sports highlights. We sat in the back row, and I made a conscious effort to look miserable so that Joanna would feel bad for dragging me along. The end of the service was, as usual, a time for sung worship and prayer ministry. Anyone who needed prayer was invited to come to the front, where a large ministry team with Cheshire smiles was waiting like cats around a fish bowl.

Suddenly there was a strong hand on my back and one to match on my chest and I heard the murmur of a prayer language to my left. Peeking out of the corner of my eye I was surprised to see my Vicar had snuck up beside me to pray for me. My surprise continued as he began to pray for healing in Jesus’ name. He moved his hand from my chest to my head, his fingers pressing against my sinuses. Immediately I felt unusual heat on my face, and I felt at once rooted firmly to the ground yet almost weightless. I don’t know how long he prayed, but when he finished he asked me how I felt. “I feel great,” I responded, and I wasn’t lying. I was healed. I didn’t start feeling better or feel only a little bit better. Immediately the pressure in my sinuses was gone, along with the ache in my throat and my general feeling of illness.

I was happy about this, but I also remember being unsure about how to feel. I kept expecting my cold to come back, perhaps after the emotions of the service had died down, but it did not. I remember wondering what God was teaching me about his healing and feeling that I should be praying more frequently for people to be healed. And I did. Sometimes people said they felt better after my prayer, but not usually. I prayed for my sister who is plagued by epilepsy. She takes medicine daily to keep her seizures at bay, and she has been praying to be healed for many years with no change.

It is written in the book of James that “the prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective.”[10] Clearly that wasn’t me. But then a couple of years after my head-cold-healing experience, my Vicar ran off with his young assistant, leaving his wife, kids, and ministry behind. It didn’t seem very righteous. Is he a philandering fraud, or is he, like Peter, full of faith and spiritual gifts, but also full of weakness and impulsivity? Why would God heal me of a head cold through this guy’s prayer while others, like my sister, continue to suffer?

***

In contrast to Peter’s passionate doubt, Thomas is an excellent example of the standard cerebral questioning usually equated with doubt. Though both men left everything to follow Jesus, Thomas might be listed just above Judas in a ranking of disciples, while Peter, James and John get top billing. Thomas is skewered for saying that “unless I see the nail marks in His hands and put my fingers where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it.”[11] We are taught to view this as cynical, weak, even faithless. But in making this proclamation, Thomas is only demanding that which the other disciples had already received. In the Gospel of John and even more graphically in the gospel of Luke, Jesus not only appears to his disciples while Thomas is not present but also shows them his hands and feet. The risen Savior even eats something to prove His authenticity. Thomas is not left to wallow in his doubt, rather Jesus appears again and reveals himself specifically to Thomas. After his own encounter with risen Jesus, Thomas proclaims “My Lord and my God!”[12]

The response of Jesus after Thomas makes his good confession is the cornerstone upon which the church condemns doubt: “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”[13] Traditionally this verse is seen as a reprimand of Thomas, and all of us who struggle with belief in our unseen God. Yet Thomas is one of over 500 people Jesus apparently appeared to after rising from the dead. Is Jesus condemning all those to whom he appeared?[14] What if we are reading this wrong? What if the emphasis should be on the incredible blessing it is to have faith in the invisible God? Faith is a gift, not a white-knuckled mountain climb. We agree that none of us deserve the grace we receive in Christ; it must be a freely given. Why do we still treat faith as our way to prove we are worthy of this grace? “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

Blessed, not rewarded.

***

I’m glad I didn’t pretend to receive some gift of joy by joining in with the laughter that I didn’t understand. I’m also thankful for my personal experiences with God of healing and suffering that I can’t rationally explain. I continue to doubt and I continue to act in faith. This can feel like a contradiction, but I think it is more honest than either pretending my doubts do not exist or allowing them to keep me paralyzed, unable to pursue the divine in ways that risk my own intellectual comfort.

Tennyson wrote, "There lives more faith in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds." I hope this is true. Despite my doubts, I know that I belong in the boat with the 11. I am convinced that not all of us are designed to walk on water, to slay the giant with a sling and stone, or to go to Pharaoh and command “let me people go!” We may long for the zeal and faith of David, but most of us more often play the part of the Israelite foot soldiers shaking in our sandals in the shadow of a taunting giant. Does this disqualify us from acting in faith?

Peter is the only disciple to follow Jesus into the temple courts when he is tried. Thomas is the only disciple to be absent when Jesus first appears to the group after the resurrection. But, it is Peter who denies Jesus and it is Thomas, one of the 11 in the boat, who first speaks the words “My Lord and my God” upon encountering the risen Christ. Is Peter really the rock? He certainly sank like one. But, what requires more faith, to risk or to wait? To go or to stay? To get out of the boat, walk towards Jesus and sink, or to remain in the boat, in the storm and wait for Jesus to meet you there? Wasn’t the great commission given to the impulsive Peter and the circumspect Thomas alike, along with so many other imperfect people like us?

Perhaps becoming a person of faith is metamorphosis and doubt the cocoon in which our faith grows. But it also isn’t quite as clean or linear as that. If we are honest, we must admit that our faith ebbs and flows like the tide. To pretend that we as followers of Christ have put our doubts behind us is not an act of courage but of denial. Faith is to step out or remain following the God we see “ in a mirror, dimly.”[15] There is not a perfect archetype of faith because we are each called to follow uniquely even as we are uniquely made. So whether we make a big fuss and ask Jesus to call us out upon the water, or whether we stay with the other 11, may God give us the faith to get in the boat, with our doubts, whatever storms there may be.

[1] 1 Thessalonians 5:24

[2] James 1:6-7

[3] Book by John Ortberg, published by Zondervan. On the back cover it reads: “You’re One Step Away from the Adventure of Your Life/Deep within you lies the same faith and longing that sent Peter walking across the wind-swept Sea of Galilee toward Jesus/In what ways is the Lord telling you, as he did Peter, "Come"?

[4] Mark 1:19-20

[5] John 11:8

[6] John 11:16

[7] Matthew 14:28

[8] Judges 6

[9] Matthew 16:17-23

[10] James 5:16

[11] John 20:25

[12] John 20:28

[13] John 20:29

[14] 1 Corinthians 15

[15] 1 Corinthians 13:12